writing

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: Why avoiding a nuclear winter shouldn’t mean a return to biological weapons

In its most recent edition, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has published an article that moots the idea of finding an alternative weapon for deterrence. The author suggests replacing nuclear weapons with non-contagious biological weapons. These biological weapons “could work well if deterrence requires threatening large human populations” or to put it another way, for states, in contravention to international humanitarian law, to deliberately target major civilian centers with horrific indiscriminate weapons, that themselves have been banned under international disarmament law for over 40 years.

In his article “Deterrence of Nuclear Winter,” Seth Baum of the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute postulates that the biggest threat from states' large nuclear arsenals is that of nuclear winter and thus there is a need to examine the potential of viable alternative "nuclear winter-safe" weapons systems to replace nuclear arsenals. This, he argues, would enable states to dramatically slash their nuclear weapons capabilities to all but nothing – a mere 50 worldwide.

Baum’s "range of candidate weapons [which] could conceivably achieve the same goal [deterrence] without risking global catastrophe," is based on several ‘attractive’ characteristics that such alternative weapons should possess, namely:

a) no significant proliferation risk;

b) affordable, technologically feasible, and politically acceptable;

c) would not significantly shift geopolitical power or destabilize the international system; and,

d) potential for use as a "retaliatory second-strike weapon, which is crucial for deterrence."

(I want to set aside here the apparent inconsistency of a weapon that is affordable and feasible yet poses no significant proliferation risk – perhaps this is because everyone already has the capacity so the proliferation is as bad as it could possible get?)

One weapons system that is apparently a ‘stand out’ candidate in fitting the bill is that of ‘non-contagious biological weapons’. This is a false dichotomy. All bioweapons are banned under the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) -- a ban celebrating the 40th anniversary of its entry into force this month (#isntitironic). Although the article does not mention this key piece of international law, there is no distinction within the convention between contagious and non-contagious biological weapons. In fact, the treaty explicitly includes toxins - the poisonous byproducts of biological processes that are themselves not able to be passed from one victim to another. Additionally, it was largely the ‘non-contagious’ agents that led to the ban. The mainstay of state-run biological weapons programmes in the past, anthrax, is itself largely non-contagious. As states around the world have unequivocally turned their back on these weapons, it is clear that they are not, in fact, ‘politically acceptable’ much less so from a humanitarian, moral or ethical standpoint.

We know from the past what happens when one state invests in a new type of weapon. Others follow suit. The history of past weapons programmes illustrates positive feedback loops of proliferation around biological weapons. (If you are interested, the James Martin Centre for Non-proliferation studies has a handy table of known or suspected past programmes.) There is a significant risk of horizontal proliferation. History suggests that if the nuclear weapon states were to develop a biological weapon deterrent, others would too. Avoiding this proliferation was, it has been suggested, one of the major reasons that the US abandoned bioweapons in the first place.

Equally, as ricin letters incidents in the US and the UK’s first conviction under its anti-bioweapons laws illustrate, there is already a significant risk of ‘non-contagious’ bioweapons proliferating vertically into the hands of non-state actors. Imagine how much worse this would be if major world powers showed such unequivocal political support for these weapons.

Bioweapons might well be affordable and feasible (although there are those that argue against this). There are certainly indications that developments in science and technology are lowering some barriers to these weapons and changing the nature of others. It has been suggested that capabilities that used to be the preserve of states are now within the grasp of sub-state actors. Should reopening the door to biological weapons lead to significant vertical proliferation, we would end up with terrorist organizations with a comparable militarily significant weapon to states. THAT’s not going to destabilize the international system, right?

Furthermore, at its heart, this article is arguing that a nuclear winter must be avoided at all costs. That cost might be completely undermining and overturning an established ban treaty. This itself poses two very significant threats to international peace and security. First, would be the loss of the BWC which remains the only complete ban of a weapon (no exceptions, no excuses, no possessors, no loopholes). Second, by encouraging states and non-state actors to look again at a weapon that has already been categorically banned under international law, it is implied that international norms and safeguards are transitory and, ultimately, meaningless as they can be overturned. In both cases, there is a major impact on the international system.

In sum, biological weapons would not make a deterrent sufficiently attractive to tempt states away from nuclear weapons, but to pursue such a capability would undermine the international norm against the use of disease as a weapon and the treaty that upholds the norm. Further, such a move would not be accepted or countenanced by the international security or humanitarian communities at large – to think that they might is out of step with both state and civil society positions. While I fully support thought experiments that challenge entrenched thinking and positions and engender well-reasoned discussion on options no matter how controversial they may be, the idea of robbing Peter to pay Paul is flawed and dangerous.

Wednesday, 11 March 2015

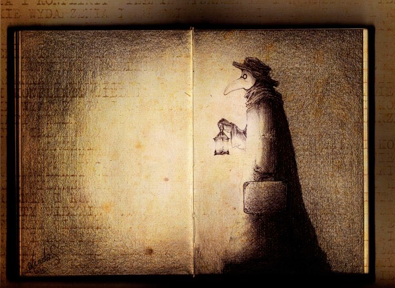

photocredit: MizuSasori

Used under a Creative Commons License, see:

http://www.deviantart.com/art/Book-about-Plague-Doctor-206493454