writing

Biosynthesis of opiates & the need to safeguard biology as a manufacturing technology

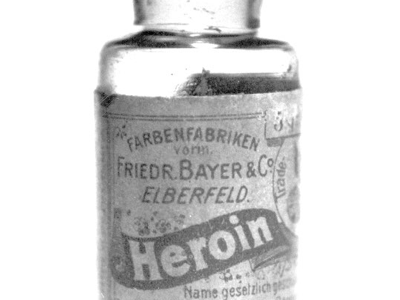

This week saw the publication of the final piece of the jigsaw needed to synthesize opiates in yeast. The new publication describes the metabolic engineering needed to produce the first half of the pathway. It supplements an earlier publication from April that describes engineering the second half of the pathway into yeast and a Ph.D. thesis that describes joining the two sections together.

Being able to synthesize such important medical tools in a more cost effective, secure and stable environment offers many benefits for our societies (from the economic, through the political, to direct heath benefits). This is a prime example of how biology as a manufacturing technology can disrupt traditional markets.

The roadmap for producing drugs in yeast is now clear. This approach is becoming a reality. Putting the pieces together and then optimising the system is the remaining hurdle. As an author from the recent paper has asserted:

““I don’t want to undersell how much work there still is to do, but I don’t want to undersell how short that work is,” Dueber says. Even when the entire apparatus has been incorporated into a single strain of yeast, efforts will still be needed to make the fermentation processes efficient. In theory, once that work is done, anyone who could obtain the engineered yeast strain would be able to make morphine in a process that is no more complicated than home-brewing beer.”

Of course, concerns were raised from the outset that such research would also enable novel production options for illicit narcotics or the use of pharmaceuticals for recreational purposes. There has been past work to engineer into microbes the metabolic pathways to produce an active compound in cannabis and a precursor of LSD.

This research is also a prime example of the importance of securing the bioeconomy. The emerging debate over the implications of this research highlights … issues which Biosecure identifies as critical to the future of the bioeconomy.

1. Taxonomic list-based approaches to identifying risk are inadequate.

Traditionally we have tried to identify the bits of biology we are worried about someone misusing in ways we are not happy with by thinking about the organism from which they come. For example, the Anthrax letter attacks in the US in 2001 led to many countries worrying about how this B. anthracis could be used to cause harm. That led to a tightening of restrictions over its use and movement. However, it has been well established that the biological properties that are cause for concern with this pathogen are often absent in B. anthracis but present in close relatives not covered by existing regulations. In relation to the opiate metabolic engineering, none of the sequences are included in regulations against misuse. With this week's paper, key functions were drawn from beetroot and soil bacteria. As we have previously argued we need to start working towards basing risk analysis on function rather than origin.

2. There is a need for active engagement during the optimal risk window.

This week's research is an excellent example of a deliberative effort to consider the societal implications of work after its demonstrated feasible but prior to a mature technology coming into existence. Following past efforts for similar engagement for synthetic genomics, synthetic biology, CRISPR/CAS9, and gene drives, it does seem possible to identify such a window in practice. Furthermore, given the active outreach by scientists and policy specialists in each of these cases, it seems as though the scientific community has identified the needs (and benefits) to be had from such engagement. It is to be hoped that policy processes and public discourse can keep up.

3. Distributed production changes how we try to keep ourselves safe and secure.

Many of our efforts to keep researchers, scientists, the societies in which they work and the environment safe and secure are centred around policing a limited number of facilities, involving a relatively limited number of individuals, all of whom share a formalised education and (to a greater or lesser extent) shared values, goals and norms of conduct. Moving towards a world where the technology is used in orders of magnitude more places, by many more people, with a much more varied range of backgrounds, interests and motivations will challenge the scalability of current arrangements and may well require a radical rethink of the underpinning assumptions.

4. A robust bioeconomy will challenge what it means to be safe and secure.

Past consideration of safeguarding biotechnology have centred on GMOs (preventing environmental damage), biosecurity (preventing use as weapons) and laboratory biosafety (preventing accidents). Solutions employed have been stop gap measures to respond to developments and largely borrowed from elsewhere (such as from nuclear security for biosecurity) or based upon expert's best guesses rather than research (as was the case for much of laboratory biosafety). This recent research illustrates that safeguarding the bioeconomy in the future is more nuanced. Safety and security measures will need to address a much broader Rangers topics, including issues around narcotics and the recreational use of biotechnology. We will need to address the issues a great deal more systematically. In line with the above principle, as we can see already that biology is being used much more regularly and in interesting ways as a manufacturing technology but has yet to come to its full potential - now is precisely the time to initiate such efforts.

5. Greater awareness over the risks and benefits of such work us a must.

Concepts of a small group of people being able to effectively police a much larger group's use of biotechnology may not be scalable. We must move from a paradigm where those developing and using biological technology are viewed as part of a problem for our societies to one where they are the core of solutions. If we stand any chance of doing this, a great deal many more people need to engage with discussions over what is (and what is not acceptable) to our societies. It is no longer acceptable to outsource this responsibility, whether it be to government officials, scientists themselves, or advocacy groups with particular agendas. The public writ large (a group of which I consider myself and you to be members) is capable of a much more nuanced understanding than often credited. For example, we live everyday with an understanding that all our actions come with associated risks and that some risks are higher than others. Equally we accept certain risks for the benefits they offer. For example, it is well known you are more likely to be injured in a car accident driving to the airport than once you are on the plane. That does not stop us from driving there. It also does not mean that our governments must stop us driving to the airport until we can prove there is no risk. Good thing too, I live too far away from my local airport to make an early morning flight.

Tuesday, 19 May 2015

Piers Millett

photocredit: Mpv_51 Image in public domain, see:

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayer_Heroin_bottle.jpg